Dr Toby Jenkins, author of "My Culture, My Color, My Self: Heritage, Resilience and Community Among Young Adults" response to racial discussion on Trayvon Martin case. In the wake of the many conversations regarding race, stereotypes, and culture that have occurred as a result of the Trayvon Martin verdict, Dr Toby S Jenkins’ recent book, “My Culture, My Color, My Self” (Temple University Press, 2013) sheds light on how young adults of color think about and approach race and culture. Rather than compiling thoughts and perspectives from educators and experts, Jenkins spent five years talking directly with young adults—African American, Latino, and Asian men and women ages 18-21. This book shares the stories and a synthesis of what can be learned from them. Excerpt From Book: The books and articles that I read preparing for this project warned of the complicated and often contentious relationship between culture, race, and ethnicity. They are distinct yet similar, separate but still broadly tied. Racial identity is an important aspect of the development of a person of color. However, it very rarely escapes the tendency to frame identity based on categorizations of skin color and how individuals experience or interpret life based on these racial experiences. Race has been seen as “a surface level manifestation based on what we look like but that has deep implications in how we are treated.” Culture and ethnicity come from within (derived from the family and community). Race comes from without (derived from society). These terms are sometimes used interchangeably though they hold very different meanings. A statement by Simone de Beauvoir best captures the nature of culture, race, and ethnicity as processes, “One is not born white, but becomes white. One is not born a Latina, one is not born Norwegian, Arab-American, Afro-Caribbean, but becomes that.” We become “white” or “black” by learning about race from society and learning the positive or negative stereotypes associated with these labels. In my conversations with young adults of color in this book, their stories affirm that culture and race intersect but are still separate roads along which people of color travel through life. Racial issues were most often presented as very negative and unacceptable. From psychologically damaging racial experiences to family members being in physical danger because of racial prejudice, race was yet another externally imposed struggle to overcome. For some, racial lessons came from their family’s past. Keith, an African American male college student, relates the stories told to him by his grandfather: “My grandfather told me there were times when some white person would try and fight one of his siblings and all of his brothers and sisters would be there for one another. His dad, my great-grandfather, got shot and killed when he was young. He got shot for fighting a white man who hit one of his daughters.” As a young child, Keith learned of the physical danger that race often presents. He tells how he was warned to be careful in the world, particularly when interacting across racial lines—careful negotiation of race was literally a matter of life or death to his family. His story, like those of many of his peers, illustrates how negative issues of race often made culture (community and family) even more important. In his example, when facing racial threat, the cultural bond of family offered protection by “being there for one another.” And what the young adults in this study affirm is that racism is unforgivable. They are insulted by it, oppressed because of it, and psychologically hurt as a result of it. Young people were less forgiving of racial discrimination. In many ways, their stories show that if race is considered to be a storm that people of color must weather, their culture was seen as a shelter from the storm. Culture, in the form of family and community, looks out for us, defends us, fights for us, and teaches us how to navigate a racist society. Interestingly, one of the most racist institutions named by young adults is the American school system. This is a bit scary when you consider that this is the environment in which the majority of Americans learn to interpret the world. Many communities of color have had histories of negative experiences in schools, but African American men have had one of the most contentious relationships with the field of education. America in general, and schools in particular have very strict codes of acceptable behavior. If you look, act, or behave a certain way it can quickly be labeled as unacceptable or deviant. In a broad sense, we groom students to play a very docile, silent, and inactive role in school. Good students are ones that do not “talk too much” or “act out.” And in recent years, Zero Tolerance policies have shown that there are potentially long and hard consequences for those students that are labeled a “troubled” (Echolm, 2010). All students with a challenging spirit and an inquisitive nature may find conflict with the social rules of conformity present in education. But, African American male students have particularly felt the weight of educational cultural norms that privilege silence, obedience, and system agreement. Though not the sole cause of attrition, this tendency to punish students that challenge classroom practices and to reward silence and conformity is just one of the many issues that contribute to the alarming drop out and suspension rates of young black men. The negative relationship between black males and school systems is an issue that has been steadily growing over the last 20 years. Perceived stereotypes about the way black boys dress, behave, speak…the music they consume, the clothes they wear, the way that they express emotion, insecurity or fear seems to translate to a threat for many Americans. In Garibaldi’s (1992) study of the New Orleans public school system, he found that although Black male youth only represented 43% of the educational community, they accounted for 58% of the non-promotions, 65% of the suspensions, 80% of the expulsions, and 45% of the dropouts. In 2010, The Shott Foundation published, Yes We Can, The Schott 50 State Report on Public Education and Black Males, revealing a national graduate rate of only 47% for African American male high school students. The following is shared in the report’s conclusion: The American educational system is systemically failing Black males. Out of the 48 states reporting, Black males are the least likely to graduate from high school in 33 states, Black and Latino males are tied for the least likely in four states, with Latino males being the least likely in an additional four states. To add insult to injury, Black male students are punished more severely for similar infractions than their White peers…(p.37). Race, class, and cultural differences undoubtedly play a role in this dissonance between student and school. But these factors do not excuse bad behavior. Race and problems with the culture of schools do not erase the reality that all boys are often socialized to be aggressive and external environments repeatedly fail to correct wrong doing. Several years ago, I personally served as a fraternity house director for an all white male fraternity at my university. I was a young black woman living in a house with all white men ages 18-21. Aggression, hyper-masculinity, machismo, etc were seen in that house on a daily basis. On fraternity row, we constantly dealt with campus judicial issues related to alcohol abuse, rape, and physical violence. Yet White men aren’t stereotyped as threatening as often as their black male peers. Pop culture often has a large and subliminal influence on how we are socialized to form ideas about men, women, gender roles, marriage, and relationships. Repetitive messaging and portrayals of women as gold diggers and manipulators or controlling dictators in relationships make some men believe these things and teach some women that to act in such ways is expected. One of the best examples was a controversial Pepsi commercial shown during the 2011 Super Bowl. The commercial features a black couple in a series of day-to-day situations in which the wife seriously harasses, belittles, and demeans her husband. With each scene we are shown a message that ultimately communicates that black women drain the joy out of a man’s life. The commercial ends with the couple sitting on a park bench when a young and seemingly carefree white woman jogs up and sits on the next bench. The husband looks at her with the first lasting expression of joy and happiness that he has shown in the entire commercial (every other time he is about to experience a moment of joy his wife comes in and steals that moment). This other woman is superficially opposite to the African American woman—she is white, she is younger, she is fit (as she jogs while the black woman is sitting drinking soda). And so the message is that she is a refreshing departure from the dry marriage to which he is obligated. The commercial concludes with the black wife throwing her soda can at him and mistakenly hitting the white woman. And so the last scene is the culmination of the anger and hostility that society believes to be present in black women—she will control you and harass you, and she is capable of violence. Many folks laughed at this commercial, and I am not suggesting that this one commercial is responsible for the high levels of misunderstanding and negative opinions of men and women of color. But I am firm in my belief that it is just one of several examples of the ways that we have been socialized to accept and laugh at negative imaging of ourselves. Mass media surround us, and we now often pay to receive cable messages that are racist, buy tickets to movies that are sexist, and pay for admission to social functions that are classist. We have more access to society than ever before, and the result of that access has not necessarily been all positive. Never before have people so widely invested in their own oppression. And too often, we do not see how these structures subtly impact and influence our thoughts, priorities, beliefs, and values. In past journal articles, I have sought to shed light on the larger historical context that has shaped the educational experiences of people of color—to illustrate that social exclusion hasn’t “just happened upon” people of color it has been a steady and intentional process. The factors that might affect why many young black men, for example, don’t finish or even get to college are numerous and have been building for years. In my article, “Mr. Nigger: The Challenges of Educating African American Men in America,” I discuss several issues that have contributed to why black men in contemporary society might be called “mister” but are in many ways still treated with a niggardly regard. Some of these factors include America’s racial past; community based poverty, crime, and addiction; a failing pubic school system; shifts in the criminal justice system; dysfunctional family structures; and media/pop culture’s impact on self concept. In his book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community, Martin Luther King Jr. (1968) foreshadowed the growing frustrations of young adults: “If they are America’s angry children today…it is a response to the feeling that a real solution is hopelessly distant because of the inconsistencies, resistance, and faintheartedness of those in power (p. 34).” History has taught a black man that his life is at threat in the presence of a white man—through death, incarceration, or even being denied opportunity professionally. History has seen our grandfathers swinging from trees, burned at the stake, attacked by dogs, beaten by police. A contemporary society has seen our uncles, fathers, and brothers kicked out of schools, jailed, racially profiled, and shot at will by police. All of this contributes to why a young black teenager would view a white man following him as a threat, as a “creepy ass cracker.” It is also telling that based on his color, dress, and gender Trayvon could be more quickly identified as a “thug” rather than kid, student, or someone’s son. Gross misunderstanding, stereotypes, and a lack of truly living together causes none of us to truly trust one another. A racist society causes us all to live in fear.

8 Comments

I recently rented the film by Michael Moore (2009), “Capitalism: A Love Story.” What I most love about Moore is his consistent show of patriotism for our country. Yes, I said patriotism. He consistently does the difficult work of loving our country enough to criticize it in hopes of making it better. His films consistently touch on the need for everyday people to exercise their democratic rights. As a college professor, I am constantly working to energize this generation of young adults to engage the principles of active citizenship. And so, I could not help but to think about college students as I watched. The movie brought up memories of student protest from this time last year. Fall 2009, like many fall semesters was filled with the energy of the start of a new school year--energy fueled by expectation. I am referring to the expectation for schools, universities, and communities to live their values. In my local area, college students at Howard University and brave youth from area high schools in Maryland were all demanding change. Having worked in the past on the other side of campus, within administration, I know how easy it is for administrators to see these students as agitators...to see protest as a problem. It is actually a solution…a wake-up call. And I’d argue that those students that dare to protest are showing more school spirit than those that simply attend every football game, wear paraphernalia, and yell their love for their school with all of their might.

In a broad sense, I am concerned that our country raises citizens that are not taught how to be critical thinkers—to question, to learn, to criticize the status quo. As a citizen, I love my country like a mother loves a child. You love your child so much that you don’t want to see her do wrong and so you discipline and correct every wrong turn. We correct our children out of love. So why don’t we see people that take that same approach towards their country, on their campus, or in their high school as being true patriots? Instead, we define patriotism through kind and pleasant words rather than strong and bold action. In a broad sense, we groom students to play a very docile, silent, and inactive role in school. Good students are ones that do not “talk too much” or “act out.” And in recent years, Zero Tolerance policies have shown that there are potentially long and hard consequences for those students that are labeled a “troubled” (Echolm, 2010). All students with a challenging spirit and an inquisitive nature may find conflict with the social rules of conformity present in education. But, African American male students have particularly felt the weight of educational cultural norms that privilege silence, obedience, and system agreement. In his article, “The Trouble with Black Boys: The Role and Influence of Environmental and Cultural Factors on the Academic Performance of African American Males,” Pedro Noguera (2002) offers the following situation as an example of how schools often push students to conform: A recent experience at a high school in the Bay Area illustrates how the interplay of these two socializing forces - peer groups and school sorting practices - can play out for individual students. I was approached by a Black male student who needed assistance with a paper on Huckleberry Finn that he was writing for his 11th grade English class. After reading what he had written, I asked why he had not discussed the plight of Jim, the runaway slave who is one of the central characters of the novel. The student informed me that his teacher had instructed the class to focus on the plot and not to get into issues about race, since according to the teacher, that was not the main point of the story. He explained that two students in the class, both Black males, had objected to the use of the word "nigger" throughout the novel and had been told by the teacher that if they insisted on making it an issue they would have to leave the course. Both of these students opted to leave the course even though it meant they would have to take another course that did not meet the college preparatory requirements. The student I was helping explained that since he needed the class he would just "tell the teacher what he wanted to hear (http://www.inmotionmagazine.com/er/pntroub1.html). Though not the sole cause of attrition, this tendency to punish students that challenge classroom practices and to reward silence and conformity is just one of the many issues that contribute to the alarming drop out and suspension rates of young black men. The negative relationship between black males and school systems is an issue that has been steadily growing over the last 20 years. In Garibaldi’s (1992) study of the New Orleans public school system, he found that although Black male youth only represented 43% of the educational community, they accounted for 58% of the non-promotions, 65% of the suspensions, 80% of the expulsions, and 45% of the dropouts. In 2010, The Shott Foundation published, Yes We Can, The Schott 50 State Report on Public Education and Black Males, revealing a national graduate rate of only 47% for African American male high school students. The following is shared in the report’s conclusion: The American educational system is systemically failing Black males. Out of the 48 states reporting, Black males are the least likely to graduate from high school in 33 states, Black and Latino males are tied for the least likely in four states, with Latino males being the least likely in an additional four states. To add insult to injury, Black male students are punished more severely for similar infractions than their White peers…They are more frequently inappropriately removed from the general education classroom due to misclassifications by the Special Education policies and practices of schools and districts (p.37). Race, class, and cultural differences undoubtedly play a role in this dissonance between student and school. But these factors do not excuse bad behavior. Race and problems with the culture of schools do not erase the reality that boys are often socialized to be aggressive and external environments repeatedly fail to correct wrong doing. Shaun Harper, Frank Harris, & Kenechukwu Mmeje (2005) brought attention to this by offering forth a theoretical model to explain the overrepresentation of college men among campus judicial offenders. In the article, they note the many factors that build bad behavior in some young men: According to Gilbert and Gilbert (1998) and Head (1999), parents and teachers are more forgiving of behavioral problems among boys and accept the fact that “boys will be boys.” Similarly, Harper (2004) asserts that parents “communicate messages of power, toughness, and competitiveness to their young sons. No father wants his son to grow up being a ‘pussy,’ ‘sissy,’ ‘punk,’ or ‘softy’—terms commonly associated with boys and men who fail to live up to the traditional standards of masculinity” (p. 92). Gilbert and Gilbert also found that interests in combat, wrestling, and active play interferes with male students’ abilities to concentrate in school and take their teachers (who are mostly female) seriously, which often results in classroom disruptions. Interestingly, boys are over four times more likely than girls in K-12 schools to be referred to the principal’s office for disciplinary infractions, suspended, or subjected to corporal punishment (Gregory, 1996; Skiba, Michael, Nardo, & Peterson, 2002). Despite this, boys are still socialized to believe that they are to be rough, tough, and rugged, even if it means getting into trouble at school (Mac an Ghaill, 1996). Lets be clear, some black men whether in high school or college do “act out.” And as explained in the quote above, seeds of bad behavior often take root outside of the school system. However, later in the article, the authors argue for educational institutions to transform their approach to judicial affairs even when it comes to those students that are guilty of doing wrong. A move from a stiff and procedural judicial process to a more developmental and educational process is suggested (Harper, Harris, & Mmeje, 2005). This recommendation holds strong merit. Even the truly disruptive student needs to be shown a new path. Changing the spirit and tone of school judicial policy and classroom culture could hold potential benefit for everyone involved. Though many students exhibit negative, disrespectful, and disruptive behavior in school, we know that all black boys that are suspended have not “acted out” and all young black men that find themselves permanently outside of the school system are not there because of their lack of skill, bad neighborhoods, uncaring parents, and disruptive behavior. Somewhere in the mix is a failed agreement between the student and school about what constitutes being a “good” student. I know this because I often experience it as a professional of color. Beyond educator/student interactions, my personal experience in higher education has been one in which even co-workers that proclaim to advocate for social justice education often interpret criticism as confrontation and aggression. Colleagues often paint as a villain the co-worker that is willing to stand up and stand out--to point out the critical problems within the institution, department, or academic program. Rather than recognizing the deep commitment and love that it takes to challenge in an effort to change, colleagues often would rather not deal with the “problem colleague.” And so this is an issue of defining active citizenship within all of the spaces that we occupy…our country, our companies, and our communities. We must begin to appreciate those students that whisper, speak, or scream for educational change. Isn’t there broad agreement that educational reform is needed in this country? So, why does it become problematic when a single student demands this reform on their campus or in their high school classroom? Whether they are asking us to change our policies on campus hate crimes, to amend student registration procedures, or to widen the lens of our course content, students are demonstrating an outward show of activism. This is indeed how “acting out” should look. I just recently moved to the DC area. I came from Penn State University where I served as the director of a cultural center named after Paul Robeson, another great activist in history who was persecuted for challenging the politics of the day. Though many people today applaud Paul Robeson as one of the greatest global humanitarians of his time, when he was alive this country applied its full weight to crush him because of his outspoken work and criticism against segregation, lynching, and global oppression in Africa. Attacked as a communist because of his open sympathy for the struggles against oppression of all people, he was eventually called before the House Un-American Committee. At his hearing, Paul Robeson made history as the only person to directly challenge the committee. When asked at the hearing why he didn’t just leave the United States and become an ex-patriot, he said boldly and unapologetically: "My father was a slave and my people died to build this country, and I'm going to stay right here and have a part of it, just like you. And no fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear...you are the non-patriots, and you are the un-Americans, and you ought to be ashamed of yourselves (http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6440)." And of course there is also Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose model of leadership is often praised as being inclusive, peaceful, and accepting. Because of this, his work is relevant to this discussion. Contrary to popular understanding, Dr. King was not the type of man to silently accept the status quo or to engage in uncritical dialogue about his country. In his Letter from a Birmingham Jail, Dr. King spoke frankly about the necessity for critical thought and social tension to create social change. He challenged the citizens of our country to become active agents for social justice rather than passive moderates that sustain, through their inaction, the status quo. Making any entity better, whether it is a school, a company, or a country is not achieved through rhetoric that makes us feel good, but rather through action and calls to action that inspire us to do good. Here is what King (1990) had to say: “But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word "tension." I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth…I have been gravely disappointed with the…moderate…who is more devoted to "order" than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice (p.291).” My hope is that we begin to view patriotism as not being exercised through simplistic statements of blind love and praise or mild mannered actions, but instead through a dedication to doing the hard, challenging, and almost parental work of rearing and growing, guiding and developing those organizations and institutions that we love. I do believe that the ethic behind being free and open to critically challenge one’s country, college, or employer in an effort to make it better and more accountable is something to be encouraged because it illustrates authentic love. We did not give birth to the country we live in, the colleges we attend, or the companies for whom we work, but we have adopted the responsibility to continue to raise each of them (to a higher level). And like any good parent, we must be actively present, engaged, and vocal through every step they take. “I’ve fallen so many times for the devils sweet and cunning rhymes…This old world has brought me pain but there’s hope for me again”…These are words from the song "Nothing but the Water" by Grace Potter. She’s saying that it is never too late to resist, regardless of the circumstances, despite the negative or unauthentic path that the world tries to force on us. And this path is often paved in gold…it looks pretty..it shines..it sparkles. Its full of things and commodities that make us believe that we are full, whole, successful, beautiful, complete. We’ve got a bunch of superficial, meaningless things that distract us from the realities that are deflating our spirits—clothes, cars, positions, titles, catch phrases, big houses, the latest hair cut and a fabulous handbag. We’ve got things that mean absolutely nothing if we don’t have a strong sense of self. Many look the part of being healthy and whole but if you were to follow them home--communication is sparse, love is lacking, many people’s lives are depressed, generally boring. For some, a family ethic doesn’t exist. Many educated, professional, middle class Americans are poor in all of the ways that truly matter. This describes how many people both men and women are treated in America on so many levels. But in this moment, I want to talk about women and the ways that the roles and images of women have been hijacked and the incredible ways that we can and do resist.

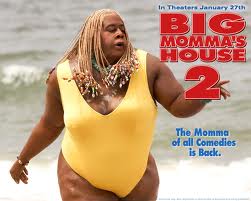

So what does a psychologically based, pop culture engineered, raping of the mind look like? I sponsored a retreat for college students called “Stirring the Pot” and students were asked to show us what messages society forces upon us about how women should be…Their work included visuals of body image, cosmetics, fashion, weakness, softness, beauty, diet, being ageless, and sex objects. This is often the American box of womanhood. These messages are so deeply a part of our culture that sometimes its hard to see them as wrong…its difficult to tease out and understand how these images move you to behave and influence the way you think in a very unconscious way. The author bell hooks talks about how if you hold your hand before a flame and absorb the heat eventually your skin will burn, if you stay out in the sun and absorb its rays you will get dark. And if you continuously absorb visual and verbal messages from movies, ads, magazines, and music it will in some way effect you…some completely follow, others become so desensitized that they can dance to it or sing it in the car. And what about those that do not fit in the box? I’m not talking about resistance yet, Im simply talking you literally and physically don’t fit the bill even if you wanted to. I’m talking about the spirit of Sojourner Truth…a woman that boldly stood up, declared, and claimed the fact that she did not fit the mold of a socially constructed femininity. And she then asked, “But Ain’t I a woman?” I guess that depends on how you define womanhood…what parameters you set on femininity. And today, I often ask this same question as movie after movie pours out of our popular culture painting the African American grandmother, the “Big Mama” figure as comical, buffoonish, and masculine. Whether it was Martin Lawrence’s Big Mama Tyler Perry’s Madea Or Eddie Murphy’s Norbit The way that women that don’t fit the mold are represented is disgusting. I read a deeper meaning. I see it signifying that to be a big, black woman is to be not seen as a woman at all—a man can play you in a movie. I’m offended by the way that Tyler Perry has made a joke of the very real racial experience that would cause an older black grandmother to carry a gun in her purse. One of my many grandmothers, Grandma Golston, ALWAYS had a gun in her purse—at Thanksgiving dinner, Christmas dinner, while walking down the street. The reasons why a black woman in the south would learn to carry a gun to protect herself and her children both outside and inside of the home are not funny. We’re talking about the realities of racial violence, a history of black women being raped, beaten, and murdered at will. We’re talking domestic violence and alcoholism…the many negative consequences that put black lives at risk—threatened. And I hear Sojourner’s whispers, “Aint I a Woman? Its not okay to present it without context—to make a joke of the women who first died before women like Grandma Golsten were taught to pack their purse. Aint I a Woman?....Inspite of all that has been put against me; despite how easy it would be to just fold and follow...to just pick up the magazine and go buy the purse; to show the skin that everyone wants to see; to cut, straighten, fry, inject, starve ourselves to conformity; to not speak up or speak out; to not question…its easier to just sing along with the song; to go see the movie and laugh…to not be so uptight. It may be costly, it may literally be unhealthy but it is easy. Its easy to just relax…we all get tired of fighting. But we don’t have to fight to resist… A few years ago, I was teaching a class on the representations of women of color. During that semester, the NAACP nationally “buried” the N-Word. The campus was all a buzz with debates about the word. So we departed from the scheduled class topic and talked about this issue. In the end, I asked everyone to think about black people as a community and throw out to me all the words that come to mind. I ran out of board space as I wrote all of the words that they shouted. I asked them to look at that board, at all of the many words that we can call each other…and asked why were we spending so much energy fighting over one. Why are we giving the negative even more face time? Why do we focus on fighting? A few years ago I was diagnosed with breast cancer. And everyone uses the language of fighting when they refer to cancer…”You’ll fight this”…”You’ll beat this!” My response was no…I’m not fighting anything. I’m going to love cancer out of my body. Meaning that I’m not just going to focus on cancer, I’m going to focus on loving those parts of my body that were so severely deprived of attention that they allowed cancer to develop. Healthier food, more exercise, vitamin supplements, meditation…Cancer developed because I wasn’t giving something inside of my body the love that it needed. You see these are two very different approaches to working against something. When we focus on fighting something like cancer we are focusing on killing cancer. And that’s what chemotherapy does. After going through chemotherapy, what I know for sure is that there is a literal war going on in your body. Chemo kills everything in sight. So thanks to the chemo soldiers you win the war against cancer but you don’t feel well in the process. It kills both the bad and good. Your body is a casualty. It wears you out. And that’s what happens when we are in a constant state of rage against the machine. We may indeed “kill” a concept or idea or stereotype but we also kill a bit of ourselves in the process. So when I talk about the ART of War, I’m not talking about a battle plan. I’m talking about authoring a formula of love. I don’t hate Tyler Perry. I hate the potentially negative consequences of his work. But it’s really not about him…its about focusing on and claiming the millions of ways that we can view womanhood, love womanhood, and be a woman. Its about giving our minds and our spirits the love they need to not be moved by anything society tries to plant there. It is a much more complex experience to deal with the internal…to wrestle with the question, “Who am I really?” “What type of woman do I really want to be?” “What type of woman do I really want to love?” “Do I truly appreciate the many dimensions of my woman friend?” “Do I truly love myself…bare and plain?” It’s an issue of the spirit. And it’s through the spirit that we resist. Resistance is a gut wrenching experience. You feel its importance in your gut. It’s when the negative constructs of society are literally eating away at your soul that we are inspired to create a politic of social critique…to author a recipe of resistance. This is why I use the kitchen as a metaphor in so much of my work. The kitchen as a metaphor is a space of resistance. It is a space where everyone belongs. You know how the social gatherings go…everyone gravitates to and hangs out in the kitchen. Even those that can’t cook…can eat. There is no marginality there…everyone is welcome. But the kitchen is also a creative space. It’s a space of innovation. To take dry ingredients and give them life, give them taste, give them a new sense of purpose is an amazing thing. And this is what we can do with ourselves. That’s what Grace Potter meant when she said, “There’s hope for me again.” We can cook up a new image of what it means to be a woman. We can stir the pot of pop culture and shake loose its hold on our psyche. I love the imagery of the kitchen, of home, of family as space of resistance—philosophically and literally. Family is a space and venue through which we learn the most basic forms and images of resistance through their model and their lived experience. My mother is a large black woman…I always saw her as beautiful, intelligent, and skilled. We need to resist the notion that leaders, educators, and artisans reside outside of the homestead. My own parents never went to college but they were brilliant examples of how to make ends meet when both ends are ragged and cut short. Before Suze Orman, for me, there was Bennie and Joyce. They never made more than 40k total household income a year, but we never wanted for anything. They never had debt—ever. They never lived above their means. So when school trips, instruments, and other opportunities were crucial we could always “afford it.” They were brilliant financial advisors. And beyond that, my mother was a teacher that also sewed clothes, grew gardens, and cooked incredible meals. We didn’t go to art museums as a family but undoubtedly art was a domestic experience for me…if you saw her gardens you would agree it is a work of art. It is a show of love. It is a form of resistance. My mother, like Sojourner grew up farming and she like sojourner can labor as hard as any man. My father was never the one to do the household repairs…renovate a kitchen, fix doors or the plumbing…that was my mom. But cooking was also my mom. She fed our family by growing and cooking good food. I now realize how important cultivating health is for your family. My mother was her full and authentic self. She never felt the need to choose an identity…her success was experiencing all of it…not privileging the help that she gave others over the help that she offered to her own family. In all of my classes, I have my students write cultural self-portraits…a paper that tells their cultural life story. This has become my signature form of data collection for my research and they are all incredible to read. I thought of one portrait in particular as I prepared this speech. One student shared how his grandmother intentionally did not teach his mother to cook to ensure that she wouldn’t be confined to the role of homemaker…you can’t be what you can’t do. I understand the ethic behind his grandmother’s actions—and it is one form of resistance. It was her bold way of opening up hope and opportunity for her child. It was undoubtedly an act of love. But I do still lovingly challenge the ethic of what was being resisted. This is another way that we have fallen prey to society’s propaganda. In our society, professional life and careers are privileged and domesticity and the homestead is often devalued. The ways in which both men and women have been encouraged to sacrifice time at home so that they can overwork for their employer is draining our quality of life. In effort to experience liberation, many women began to view the home as an oppressive environment and sought more in their lives. I just question if it has to be an either career or family scenario rather than trying to embrace both work and home. I think we need to resist the idea that to spend time cooking and cleaning for your family, whether you work outside of the home or not, requires you to sacrifice who you are. We need to resist the pressure to resist the kitchen. The kitchen is one of the most important rooms in the house. It is literally the life-blood, the link to our health. I’ve spent many years transitioning to a vegetarian, organic, lifestyle. And with my significant health challenges, I know for sure that the kitchen is as important as my doctor’s office. Some days are good, some entire weeks are a challenge…but I know that in general I am doing okay because of the food that I am eating…whole plant based food, nothing processed, nothing boxed or microwaved, knowing the exact nutrients that I need each day and giving them to my body as a gift. When you are preparing a meal for your family you are doing more than just making meatloaf you are chopping, blending, and stewing the gift of life. Spiritually you are doing more than cooking a casserole you are feeding hungry bodies. And in a spirit of servitude hungry bodies count even if they are in your own home. Many folks will volunteer at a soup kitchen feeding the homeless a healthy meal and grab McDonalds for their own family on the way home. What is that? Whether they are oppressed or privileged all hungry bodies deserve healthy whole food. The kitchen is the last place we need to resist. And one of the most essential and important lessons all of us will learn is how to cook….it’s a skill that goes a very long way. Our families give us counter images counter narratives of womanhood. Our families show us that we can be all that society tells us that we can’t be and still be a woman. Because of our families we resist Through our art…whether its the artful way that we live our lives, the domestic beauty that we create in our homes, or the incredible way that we make words come alive in our conversations and cultural production…we express…we speak…we stand…we love…we laugh…we cry… and we resist. To resist such strong and deeply ingrained ideals will take a lot of arguing, talking, laughing and crying. Good thing we’ve got home training… And that’s all we really need… A few weeks ago, a friend called me on his way to work. I’ll assume it was hands-free. We had a good conversation and as he pulled up to his building, I expected our talk to end. I was still in bed and he was starting his work day-two good reasons not to be on the phone. But apparently, I was mistaken. He continued to talk to me as he entered the building, as he yelled “good morning” to co-workers, as he started to take on his first appointments…the conversation just kept going. When we finally hung up an hour later, I started to think that distracted driving isn’t the only downfall of mobile phones. We need to add distracted conversations to the list. Sure, distracted conversations aren’t that dangerous. Lives probably aren’t at stake. But trying to talk to someone that is distracted is down right annoying.

I found myself longing for the good old days at my parent’s house. When I was a teenager, I used to be so embarrassed by our telephone. I felt that we were the only house that still had a rotary dial phone with a cord. As everyone else bought the trendy new cordless phones in shades of white, grey, and black, my parents stuck to their guns. They always got the cheapest and easiest phone to operate. But you know what, I had many a good conversation on that phone. Those were the type of conversations that required you to cop a seat in a big chair, curl up in the bed, or lay out on the floor and just talk. You couldn’t cook and talk. There was no way to walk and talk. No driving, working, shopping, or running errands. You simply sat down and talked. Conversations were clear. Our minds were focused. No need to ask “Can you hear me now?” No traffic sounds, no radio music, and no sounds of footsteps. Just conversation and laughs. I miss those days. I miss the attention that is supposed to come along with a telephone conversation. It used to mean something to be on the phone with someone for a whole hour. So, I am taking a stand (probably a few steps behind Oprah’s important stand on distracting driving). I’m standing up against distracted conversations. They are all connected really.Not only are the mobile phone conversations and texts dangerous-they aren’t even good. I don’t want to talk to you while you are doing other things. I’m tired of straining to hear you because you are standing near a construction site trying to talk on the phone. I’m done trying to stick with you while you fade in and out just to finally have the call dropped completely. I’m tired of all the misspelled words in the texts that you rush to send before the light turns green. Just call me when you get home. And when you do get home, please finish all of your tasks, have a seat on the couch, put up your feet, reach for the phone, and give me a call. And I will be somewhere on the other end, laying in my bed, sitting in a big chair or sprawled out on the floor talking to you like a cord is attached and feeling like I’m fifteen again. The other day, I watched two toddlers, a boy and a girl, who were perfect strangers walk up to one another at the park and begin to play. By the time I walked out of the park they had shared laughs, helped one another make some sort of concoction in the sand, clapped for each other’s good deeds, pushed each other out of anger, and even shared hugs. They were so free with their genuine appreciation for one another’s company-no strings attached, no worries that the other might misinterpret the hug, no biting of the tongue or hesitating to share kind words. It was one of the most refreshing male/female interactions between perfect strangers that I had seen in a very long time.

As I walked home, I thought back to a conversation I had a few years ago with a man who I consider to be a colleague and a potential friend. He is someone for whom I have a great deal of respect. I’m not quite sure why my mind went back so many years but the memory came back vividly. My colleague shared with me that an email I had written him made him uncomfortable. And so, he wanted to ensure that the parameters of our relationship were clear and that I was not seeking to work with him in order to get close to him. I was initially surprised and the more I thought about it insulted. Of course I searched through my sent files and re-read every email I ever sent to this man. I finally came to one that I guessed was the culprit- a line that stated, “Can you bring some sunshine into my life please.” It is very clear how this could be misinterpreted. But here is the issue: At that time, I lived in a city that went without sunshine for about seven months out of the year. Winters were extremely long and when it was still dark and cold in April everyone was miserable. So each “spring,” I would usually go on a rant about the weather and had mentioned this weather in a few other emails that I sent to him. I wrote this email meaning the sun in the sky not the philosophical light in my personal life. No doubt, I understood why he would feel compelled to have the conversation and why it is so easy for any man to misinterpret kindness for flirtation. But still, I was insulted. Professionally insulted because of the underlying insinuation embedded in his comments-that I would use the work to which I am so deeply committed as a venue to spend time with a man. Insulted because I am the type of woman, the type of person, that works hard to treat the professional men with whom I work with the same respect that women demand in the workplace. Inappropriate behavior and sexual disrespect goes both ways. I am conscious of the fact that many outstanding, attractive, and successful men are inappropriately approached and propositioned. And so I am very careful to ensure that my interactions with men are always respectful. But at the same time, I don’t want to compromise being kind, playful, caring, and nurturing through both my work and with the people with whom I work. I want to be free to just be me rather than being made to become a cold, distant, formal, and inexpressive person. And so as I left the park that day, I found myself thinking about that little boy and girl on the playground and wishing I was back there again in my own life. What happened to good, honest, and platonic friendship? Somewhere between the playground, the classroom, and the boardroom it all gets so fuzzy. And it is disheartening. I think that I was also insulted because the very idea that I was being forward or inappropriate goes against my personal principles as a woman. I am a Southern woman. I was raised in South Carolina for the first 21 years of my life. And there are some southern values, really human values, of which I refuse to let go. As old and traditional as it may be, I believe in a man approaching a woman and so I am the type of woman that does not throw herself at men. I believe in courting, and so for me, attraction comes through knowing a person not just being around them. But most importantly, I believe in the spirit of community and familial love. I am traditionally southern in that I embrace the idea of being open and honest with your feelings, of being refreshingly naïve in a way that allows you to give a brother a beautiful compliment, smile, hug, and love without fearing that he will think that you are propositioning him, disrespecting his marriage, or hoping for anything more than a simple thank you. In the adult years that I have spent growing as a woman outside of the South, I have found it extremely difficult to just be kind to a male friend without that being misinterpreted as flirtation or a sexual advance. Yes, many women can be very aggressive, flirtatious, and some even down right inappropriate in the ways in which they interact with men. But it seems that this unfairly becomes the prejudice of all women particularly among colleagues…to share kind words, to acknowledge a man’s genius, to be nurturing and caring through a hug, to even suggest breaking bread together or sharing a cup of coffee is interpreted as an interest in something more intimate. We can’t even play together anymore much less build a healthy ethic of community. This worries me, particularly in a society that does so little to love black men on a daily basis. Because of old, patriarchal ideologies governing parenting and in an effort to groom “manliness,” young boys are not nurtured, hugged, and affectionately spoiled enough. And black men are unloved by so many institutions in American society-the judicial system, the educational system, the political system, and the list goes on. So I have taken a stand as a woman to do all I can to be guided by an ethic of love in my interactions with all of the men in my life-both personal and professional. I want to be able to freely tell a friend that I think he is an incredible man without him interpreting that statement as, “Can we sleep together.” I want to be able to hug a colleague without others supposing that something inappropriate might be going on between us. I want men to be able to have a wider view of love that allows them to see that women can love them in many more ways than just romantically. I want to be a true sister to all of the brothers in my life, partly because I never had a brother of my own. We are all familiar with the old saying that all is fair in love and war. This informal but very popular edict means that people in love and soldiers in wartime are not bound by the rules of fair play. To me, this gets at the core of what’s straining our healthy development of all types of relationships. There is so much inappropriate, unfair, and dishonest behavior going on that it clouds our ability to even recognize goodhearted kindness when it is staring us in the face-even on a computer screen. But I am holding on-trying my best to transcend the battles between the sexes. And I am going to continue to show and express my love, appreciation, and admiration for all of the men in my life including the brother that expressed his concern. I just hope that one day those men can feel comfortable loving me back as a community sister and a friend. Because, yes, women also need love, hugs, and care from everyone in their life and in every space that they occupy-the bedroom, the boardroom, the neighborhood, and the playground. Nov 12-13th is "To Write Love on Her Arms Day" a few days dedicated to those suffering from depression. So this poem goes out to all those bleeding hearts that need warmth...friendship, love, someone to hear them and to know that they matter.

Love on My Sleeve…T. Jenkins I’m just trying to be…the kind of woman that wears LOVE on her sleeve Takes her heart out willingly Gives it some air…lets it breathe Opens it up and allows it to be The kind of design that can leave Visual impressions on souls that bleed I want to stitch my heart on leather jackets that keep souls warm on long winter rides You know that kind of life that feels like your climbing mountains and crossing rivers but will never get to the other side And its cold And the bike is wobbling And you feel unsteady You're on this journey and no one even taught you how to ride You are barely- hanging -on And all you have to keep you going is the comfort of something warm So let me be that material that can take a brick chill and turn it into something cozy Im ready to deal with hard and complicated Ready to be a love that’s not easy That’s not simple Im ready to be pricked by the needle, to pick up the thimble And be the thread that stitches patterns of your life into a coat-of-armor To cover you…to help you keep riding until a new day breaks I want to create a brand name for that love called the “Dawn of Carin' For those like me, who still hope and believe in the power of love and are refreshingly naïve Enuff to wear it on our sleeves.. To learn more about the day visit this link http://www.facebook.com/pages/TWLOHA-To-Write-Love-On-her-Arms/324230271562?v=wall

Start blogging by creating a new post. You can edit or delete me by clicking under the comments. You can also customize your sidebar by dragging in elements from the top bar.

|

AuthorA lens is an object used to form images...a lens helps us to see something more clearly. Every experience, issue, or topic in life can be interpreted differently depending on the lens (perspective, background experiences) of the person facing the situation. This blog represents my critical thoughts on various topics...told from my lens on life. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed